Know your audience is a universal principle of rhetoric, any kind of rhetoric. Audience awareness is critical to making an argument work because people with different interests, looking at the world from different perspectives, and possessing some assumptions rather than others will interpret what they read or hear differently from anyone who doesn't share those qualities. Any child who ever tried to wheedle something out of one parent rather than the other knows about audience. And yet the older we get the less audience aware we may become.

And then there's the curse of knowledge, and this is by far the greatest source of loss of audience awareness. If you know how to do something really well, you tend to forget how you do it and if someone asks you how, you might leave a bunch of steps out because you are no longer aware of them yourself or assume the asker knows things they don't because it doesn't occur to you that someone might not know such things. There are also miscommunication problems caused by errors in prior knowledge, not just gaps, but mistaken mental models or broken concepts or colloquial interpretations of technical terms. The more you know, the more insider information you have, the harder it is to anticipate an outsider's point of view.

Some products create demand, most supply an existing one. Steve Jobs, who is often sited as one of the foremost build it and they will come types because people didn't know they needed a cell phone until he made the iPhone once said:

One of the things I've always found is that you've got to start with the customer experience and work backwards to the technology. You can't start with the technology and try to figure out where you are going to sell it.

On the other hand, Henry Ford is said to have said, "If I'd asked people what they wanted, they would have said faster horses.". People don't always know what they want or even have a clear idea of what they think, but that doesn't mean they are irrelevant to understanding how best to solve a problem.

Audience analysis is critical to business communication and to business itself. This is why businesses spend large portions of their annual budgets on learning about their customer's needs. In other business classes, you will likely encounter discussions about demographics and market research. In this writing class we are going to look at persona development.

A persona is a research-based representation of a segment of your audience, depicted as a real person. The research upon which a persona is based is typically done through client feedback, questionnaires, surveys, focus groups, and interviews. The information gathered should make it possible to predict behavior. A persona is not a stereotype. It is not a character, and even less a caricature. A persona is a concrete generalization that accurately represents an audience segment. Businesses use personae to make sure that everyone writing for the company -- or designing for the company -- has a clear sense of who they are writing to and working for.

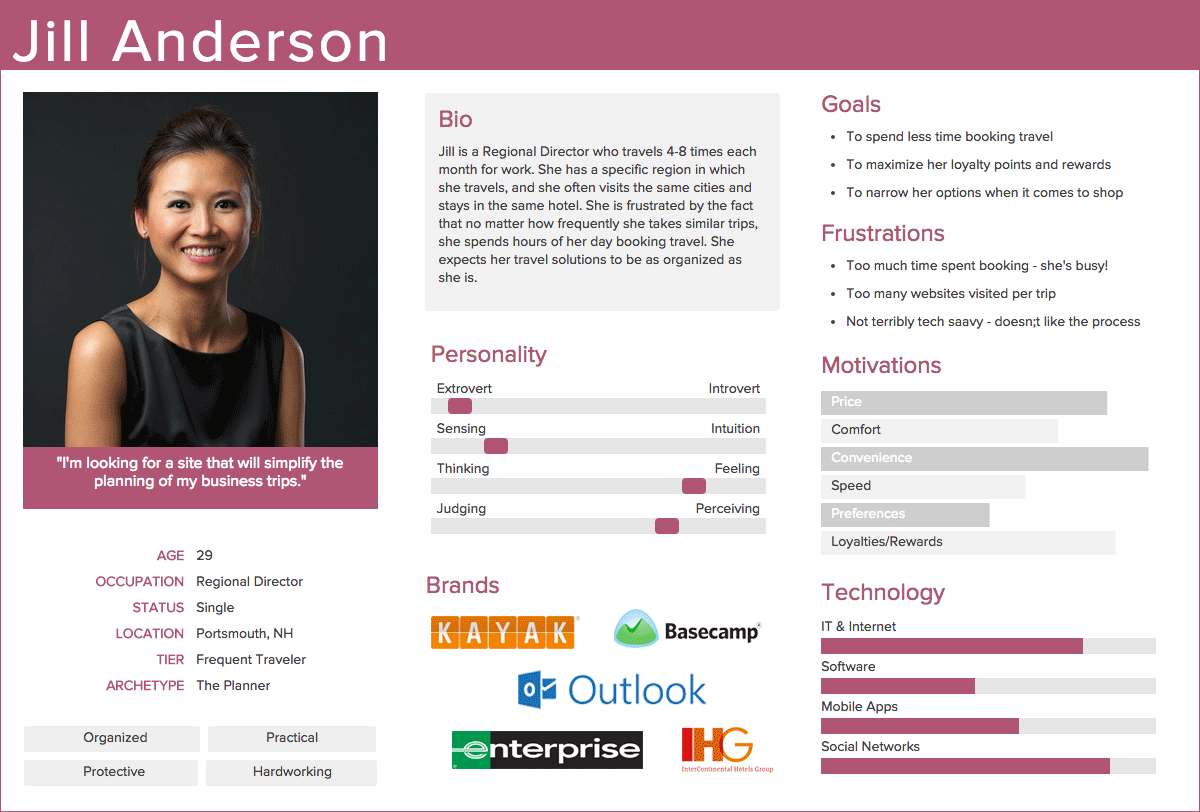

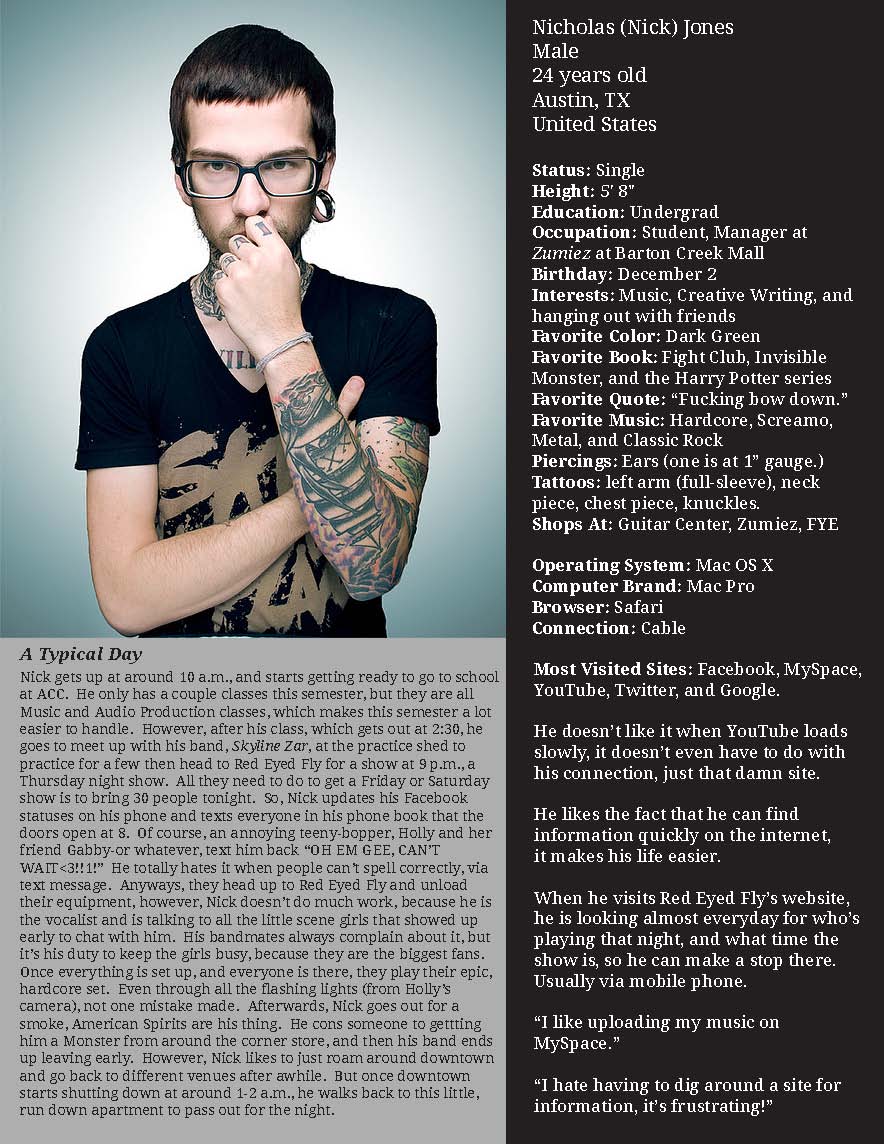

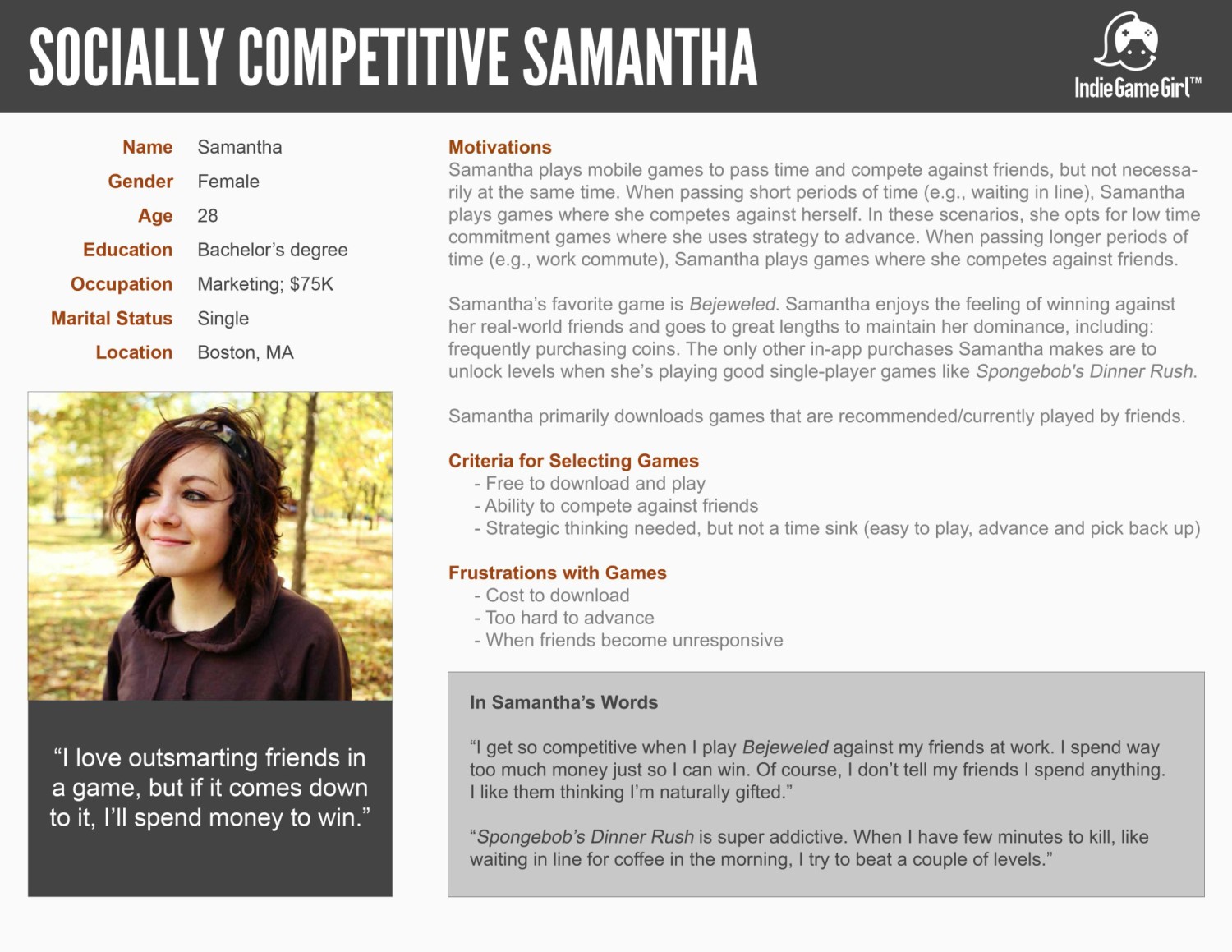

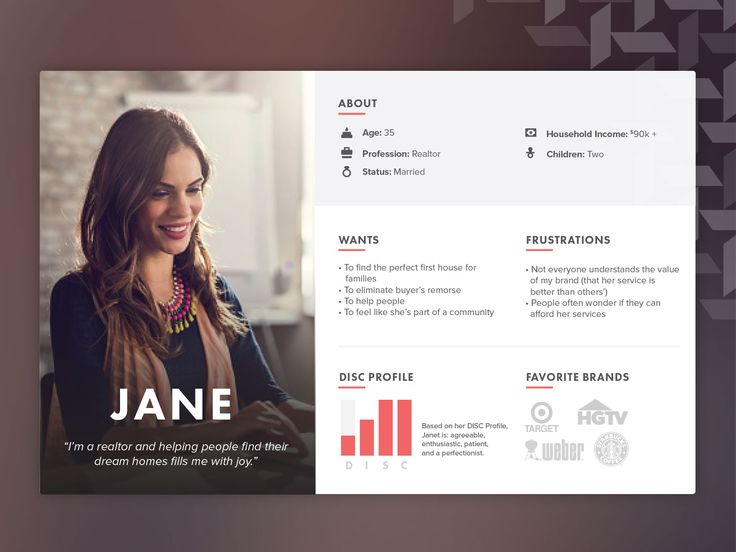

Persona descriptions tend to be attached to a photograph of an actual person. I've seen life-size cardboard cutouts with note cards taped to the wall around them. More common, though, are photos like the one on the right. The goal is to get a real sense of actual people with specific problems and attitudes so that as you write you don't just write for some abstract, disembodied, undifferentiated "audience member".

Absent a context, the examples below may be a bit hard to interpret, but look at the design and the topic headings. Each of these looks very much like what personae look like. The headings are fairly common too: demographics, motivations, frustrations, goals, brands. An important quotation from an interview or a slogan or mantra that sums up the type is also a common feature of personae. Some include personality test data (DISC assessments, for example). A day-in-the-life-of narrative is also a frequent feature. Remember that the goal of a persona is a concrete representation of a generalization of one of your market segments. If you are writing to clients, what kinds of clients do you have? If investors, what kinds of people are they?

When North Carolina State University set out to update its library, part of their research was student profiles. I am assuming these are not actual individuals but generalizations. I'm not certain.

You need multiple personae unless everyone suffers your problem in exactly the same way and there are no distinctions to be made in how the solution is purchased or applied. If one size fits all, one persona is enough. Even if your product really could be sold as an undifferentiated commodity, audience segmentation might be a way to improve revenue. You can charge rich people, for example, more for the same service, and use the increased margin there to supplement the less wealthy, or not, depending on who you are or your company is. I met someone who works for one of those large matchmaking websites and she said that if you fill out the questionnaire saying you have what the algorithms interpret as a high-paying job you will be quoted a higher monthly fee. She said you could grieve that and win, but most people have no idea it happened.

So you need to learn about your prospects. You should observe them as they are experiencing the problem your proposal addresses. You should interview some of them. And you should develop and distribute a questionnaire to get data from a wider sample in order to make sure what you think you know is real.

Having said that, however, you can start to build a persona by getting answers to some stock questions. The list below is tailored for individual people, but they would work just as well for a corporate entity.

You need a persona for each relevant person -- those who have the problem, those who are indirectly affected, those who are empowered to decide on a solution. You may need several personas for those who have the problem if it is possible to have it in different ways.

Getting the answers to these questions from real people who are potential customers will help you refine your thinking about both your planned solution and how best to propose it.

Spend some time in the courtyard or where ever GSU students are plentiful. Observe appearances and behaviors. Put together a list of "types" of GSUer. Give them a name. Describe their uniform. Describe their behavior. Focus on differentiating each group from the others. You are looking for telling differences.

Using the stock questions above, and any other relevant questions you can think of, develop personae for your intended solution. How many will you need? How will each differ? Get a photograph of a person you will use to represent each persona. Create the trait list and think about how to represent the traits with the image.